Producer and guitarist Leo Abrahams has always been hard to pin down. There can’t be many people who have collaborated with both Paolo Nutini and Leafcutter John, while his four previous albums have run the gamut from folk (‘Grape and the Grain’, 2008) to art-rock (‘The Unrest Cure’, 2007), ambient electronica (‘Scene Memory’, 2006) and songs (‘Zero Sum’, 2013). ‘Daylight’, released in November 2015 by Lo Recordings, is similarly un-categorisable, its 13 tracks existing right at the edge of song form. There are long instrumental passages; vocals, when they do arrive, are a blend of words and mangled textures. ‘It is,’ says Abrahams, ‘an album of deconstructed songs, although some are more deconstructed than others.’

‘Daylight’ combines live contributions – Stella Mozgawa from Warpaint plays drums throughout, and Abrahams’ guitar is much in evidence – with a significant dose of electronics. Brian Eno sings on one track. Abrahams has worked with Eno before, as well as with Pulp, Roxy Music and Anthony and the Johnsons among numerous others.

Abrahams’ production credits include Frightened Rabbit and Wild Beasts, and he has composed film soundtracks with David Holmes. ‘Daylight’ finds him applying some of the lessons learned from these projects. Some tracks grew out of collaborations with Underworld’s Karl Hyde and Leafcutter John; others were written alone in New York. But though by habit meticulous in the studio, Abrahams deliberately introduced an element of chaos into several of the tracks. ‘Chain’ finds him cutting up vocals and beats using a children’s toy; for ‘Steal Time’, he constructed pedal chains so complicated he was no longer fully in control of the end result.

Daylight is an extraordinary album, constantly surprising while at the same time thoroughly coherent. Whole fistfuls of genres co-exist and combine at any given moment. Abrahams’ willingness to introduce random elements is perhaps most evident on the title track: warmly immersive until the mood is shattered by bursts of what could almost be machine gun fire. Throughout, the live and the electronic are so thoroughly enmeshed as to be indiscernible. Vocals drift in and out as though behind gauze. The production is painstaking but, within strictly defined parameters, finds room for chaos as well as order.

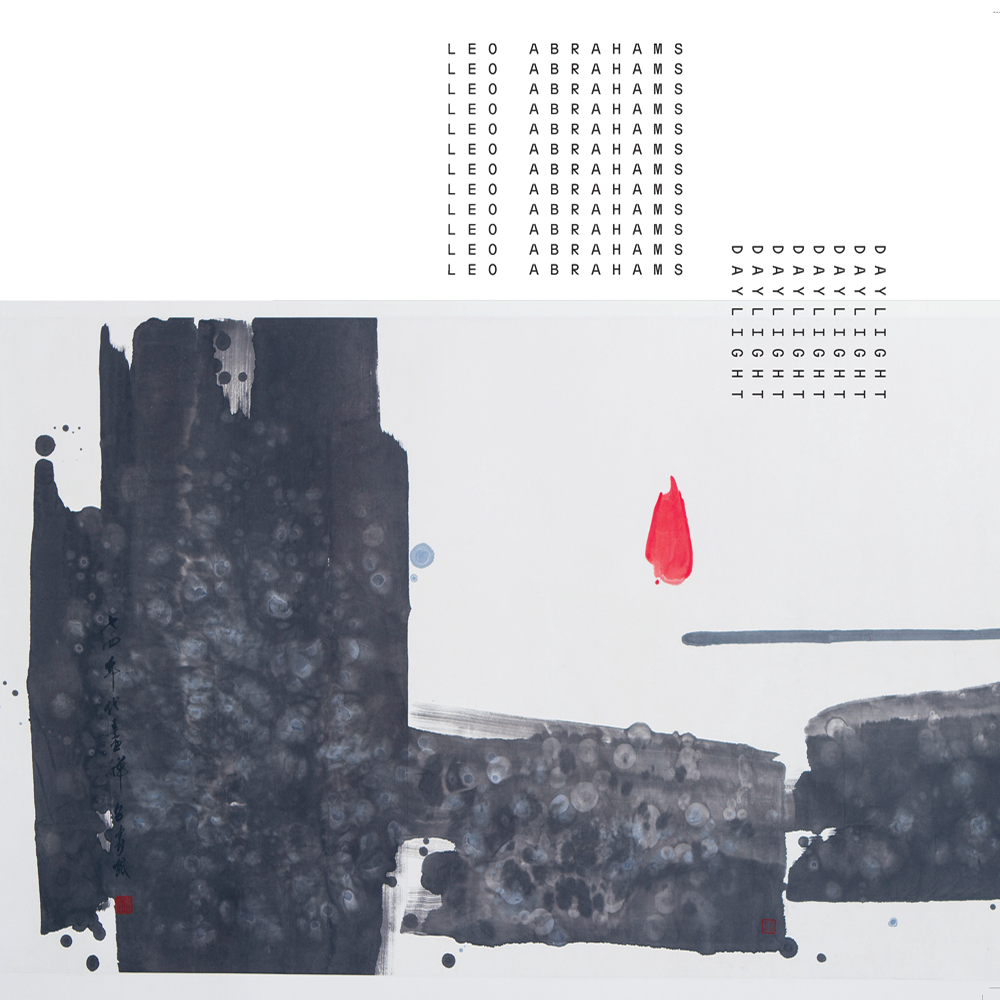

‘One influence on this was a strand of Chinese ink art which emerged in the 1960s,’ Abrahams explains. ‘A lot of the techniques involved resonated with my ideas around making music out of chance events, and they helped to crystallise my approach. I didn’t want to compose. I wanted to let things happen and then organise the results.’

The front cover of the album features a painting by Lui Shou Kwan, from his revered ‘Zen’ series. Abrahams sees a specific correlation between the lotus that sits in the centre of the image and the role of the voice in music: however vast the surrounding space, it is still perceived and understood in relation to the lotus. He also embraces the notion that material can dictate form, following on from the ways in which Chinese artists use paper and ink. ‘Composition is organisation,’ he elaborates. ‘The brain is pre-disposed to find patterns. I wanted the musical equivalent of an inkblot test: chuck stuff at the page and leave it to the brain to organise it.’